- Myths of Technology

- Posts

- Why AI-led Abundance Will Make Us Miserable

Why AI-led Abundance Will Make Us Miserable

Exploring how infinite creation might rob us of meaning, and why scarcity isn't always the enemy

Please tell me I'm not the only one shocked by this:

In Japanese Shinto mythology, the creator gods Izanagi and Izanami gave birth to a child with no limbs. They discarded the child by sending him to sea in a boat. When they asked the older gods why their child was deformed, they were told they hadn't consummated properly and that the male must always invite the female.

How did a story about incest, abandonment, patriarchy, and discrimination become the foundation for rituals of purification and sacred order?

And what does it have to do with you?

"Izanami and Izanagi" (Ogata Gekko, 1891) depicts the Shinto creator deities who birthed the Japanese islands through their divine union. The painting captures a moment of cosmic contemplation as the gods stand together beside a reflective pond, their complementary black and white robes symbolizing the fundamental duality that underlies all creation. (Courtesy: artsandculture.google)

While Shinto mythology is a universe in itself, it teaches us about valuing what we value more than all other forms of meditative reflection combined.

Why do we value the people, things, and experiences that we do, even though they are imperfect? And how does AI affect it?

What happens when AI can provide instant answers to every existential question, unlimited empathy for our pain, and a million solutions to eliminate all scarcity and suffering?

To understand, let’s go back to our history for a moment.

The Gift Economy of Meaning

Value is often associated with money, and often goes back to its origins in the barter system.

But before money existed, human societies operated on gift economies, systems where goods and services flowed through relationships, reciprocity, and obligation.

In Charles Eisenstein's "Sacred Economics," he argues that the transition from gift to commodity fundamentally altered human consciousness. When everything became property to be owned rather than gifts to be shared, we began experiencing the world as separate, scarce, and competitive rather than interconnected and abundant.

The shift to money-based economies also changed how we understood value itself. Suddenly, worth became quantifiable, comparable, and extractable from its context.

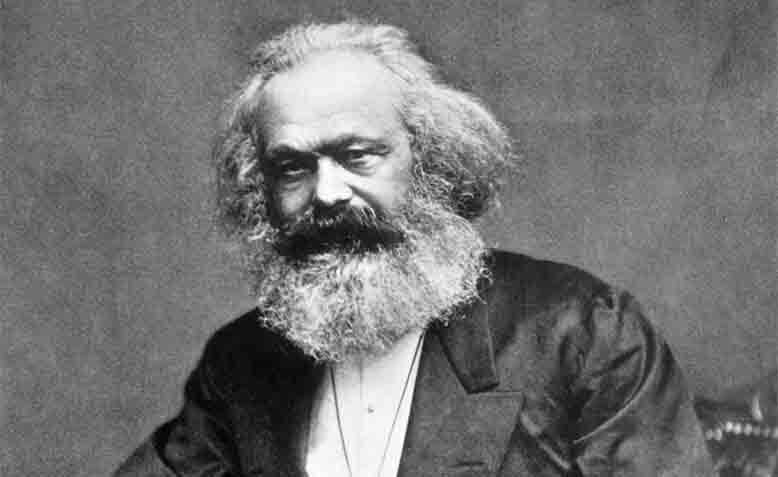

Karl Marx called this "commodity fetishism", the process by which social relationships between people become relationships between things.

Karl Marx was a German philosopher and economist who revolutionized our understanding of capitalism. Marx identified commodity fetishism, the phenomenon where we attribute mystical properties to products while forgetting the human labor that created them. This means we see a smartphone as inherently valuable rather than recognizing the exploited workers who mined its materials and assembled its components. Or we marvel at the seemingly magical abilities of ChatGPT, Gemini, Midjourney, etc., to create text and images while forgetting they're built on vast datasets scraped from human artists, writers, and creators, often without compensation. (Courtesy: counterfire.org)

This commodification machine has been accelerating for centuries. We commodified survival through agriculture, knowledge through writing, spiritual connection through institutions, and human potential through formal education. The Industrial Revolution mass-produced objects. The information age mass-produced experiences.

Now, AI is mass-producing everything that we find meaning in.

The Attention Economy's False Abundance

Today's digital economy operates on artificial scarcity, a deliberate limitation of infinitely reproducible resources to maintain profitability.

For example, Disney kept classic films "in the vault" despite digital copies being infinitely reproducible. Academic publishers charge thousands for research that could be freely shared. Software companies sell "licenses" for code that costs nothing to copy.

It is rooted in the belief that one person's access means less for everyone else, that we must compete for artificially limited resources.

But AI is dismantling even artificial scarcity. When ChatGPT can generate infinite poems, when Midjourney can create endless paintings, when code can be written automatically, we're approaching a "post-scarcity" for creative goods. It’s a state where creative goods become so abundant they're essentially free, like air.

Yet instead of satisfaction, we're experiencing psychological distress and struggling to find meaning.

So, where exactly does this abundance trap us?

The Sacred Limitations

Indigenous gift economies understood that meaning emerges from relationships, and relationships require limitations.

When the Potlatch ceremonies of Pacific Northwest tribes involved giving away or destroying valuable goods, they created limitations through deliberate sacrifice. The chief who gave away goods despite his limitations gained deeper trust and meaningful relationships.

"Raven Yakutat Tlingits at a Sitka Potlatch, Dec. 9th, 1904" captures one of humanity's most profound economic rituals, including the practice of giving until it hurts. In Tlingit culture, potlatches involved chiefs distributing their entire wealth, sometimes leaving themselves destitute, to honor the dead or celebrate life transitions. This deliberate impoverishment was a spiritual transformation where scarcity made the act sacred. The more limited the resources, the more meaningful their surrender became. They believed consciousness is enriched not by grasping more but by giving away what we have. (Courtesy: sheldonmuseum.org)

Value is more about what we choose to share over having it by ourselves, and not just supply and demand.

Viktor Frankl's observations from concentration camps explain this perfectly. In conditions of extreme material scarcity, those who survived weren't necessarily the physically strongest, but those who could create meaning through conscious limitation, like choosing to share their last piece of bread, maintaining dignity in degrading conditions, and preserving hope despite despair.

Frankl also noticed that meaning emerges not from having unlimited choices, but from how we respond to unavoidable constraints.

But what happens when AI collapses every kind of scarcity?

When AI can generate infinite "gifts", it ceases to embody a relationship because it costs the giver nothing.

Gresham's Law, a principle in economics that states that "bad money drives out good," explains the consequences the best. When cheap and valuable currency coexist, people hoard the valuable and spend the cheap, so only cheap money circulates.

This also means infinite AI-generated content (easy to produce) drives out finite human-created content (requires sacrifice), even though we know human creation is more meaningful. We're economically incentivized to choose convenience over authentic human expression, gradually forgetting why authenticity mattered in the first place.

The Return to Sacred Economics

True abundance emerges not from infinite accumulation or mass production, but from a conscious relationship with limitation.

Charles Eisenstein calls it sacred activism, or deliberately choosing constraints that restore relationship and meaning. Just as people choose to walk in nature despite cars, or cook elaborate meals despite restaurants, we must choose human creation despite AI's superior efficiency.

This means that the future economy might distinguish between "abundant goods" (infinitely reproducible AI outputs) and "sacred goods" (irreplaceable human expressions). The value of sacred goods won't come from their utility but from their embodiment of conscious limitation, human presence, and irreplaceable relationship.

The path forward isn't rejecting AI, but understanding how to preserve the economic foundations of meaning within AI abundance.

Perhaps the Shinto creation myth contains wisdom we're only now ready to understand.

Izanagi and Izanami were repeatedly punished, not because of failing to consummate properly, but for disrespecting the limitations rituals had put on them. After their child's deformity and subsequent tragedies, Izanagi underwent many purification rituals. His repentance didn't undo the consequences, but it restored his relationship with the divine through accepting, rather than fighting, the constraints. Sometimes the sacred emerges not from getting everything we want, but from choosing what we're willing to sacrifice.

As artificial abundance takes over, our most radical act might be learning that our limitations are a gift.

Which forms of difficulty will you embrace as gifts rather than problems to solve?

Reply